Mid-sized companies are reducing their dependence on China, dominating their industries and creating a roadmap to succeed in a new world economy.

Germany was the West’s biggest winner from the past 30 years of globalization. Russia provided cheap energy. Emerging markets provided cheap labor. Everyone who was anyone wanted to own a Mercedes or a BMW or an Audi. And the cherry on the Black Forest cake: The United States picked up the bill for defense while the Germans devoted all their energies to making money.

Globalization brought psychic benefits, too. Germany’s two previous irruptions onto the world stage — in 1914 and 1939 — had occurred in the name of nationalism and militarism. The new age of globalization allowed Germany to showcase its ability to work across borders in the name of universal prosperity.

Which raises a troubling question: Will the biggest winner from globalization become the biggest loser from deglobalization? The headlines are hardly encouraging. Olaf Scholz, the chancellor, has talked grandly about “Zeitenwende,” but dithered over delivering tanks to Ukraine. Many big companies are too dependent on China to rethink their strategies. China is by far the biggest market for luxury carmakers such as Porsche AG. The Mercedes-Benz Group AG’s biggest shareholder, the Beijing Automotive Group Co. Ltd., is also Chinese. With such a short-sighted strategic perspective, the German eagle can easily give the impression of being an ostrich.

But, as Winfried Weber, a professor at the Mannheim University of Applied Sciences, points out, the real engine of the German economy is not the big corporations but middle-sized companies that you’ve probably never heard of — companies that management gurus have dubbed “mighty minnows” (Tom Peters) or “hidden champions” (Hermann Simon) and the Germans call the “Mittelstand.” Germany only had 27 companies in the Fortune 500 in 2020 compared with China’s 124, America’s 121, Japan’s 53 and France’s 31. But it has more than a thousand companies that rank in the top three in their respective markets. Poeschl Tabak GmbH has 50% of the world market in snuff, for example; Flexi has 70% of the market for retractable dog leads. All told, the Mittelstand accounts for the overwhelming majority of businesses in Germany, and some 60% of all jobs.

Where Are the World’s ‘Hidden Champions’?

From 2015 to 2020, the number of German hidden champions grew by one-fifth; most are family firms that have existed for an average of 70 years.

These companies are “hidden” in three senses: They dominate tiny global niches, they prefer to keep themselves to themselves and they are usually located in small towns. Visit a random small town in Germany and you will probably find a global leader in one market niche or another hidden in a sidestreet or suburb. The secret of Germany lies “somewhere in the nowhere,” as Weber likes to put it.

A recent visit to three such companies suggested that they are adapting better to the new phase of globalization than the big companies. The last age of globalization played into the hands of the hidden champions for two big reasons: They focus on small global niches, and they provide the machines that powered the growth of the emerging markets, most notably China. The greater Shanghai region is home to more than a thousand German subsidiaries, for example.

But they are not making the mistake of remaining stuck in aspic. They are thinking hard about what the new geopolitical landscape means for them. And they are rapidly rejigging themselves to meet new challenges and seize new opportunities. Beneath the deliberately mundane surface of the Mittelstand, a hidden revolution is taking place.

Herrenknecht AG is the western world’s biggest tunneling company. (Elon Musk’s Boring Company may have the catchier name but it’s small-bore by comparison.) A giant drill bit on the company’s campus celebrates its triumph in boring the 57-kilometer Gotthard Base Tunnel. The in-house tunneling academy contains an exhibition of the machines it used to dig the Doha underground. The factory is constructing three very visible tunneling devices for the moment: one for a tunnel under the Panama Canal, one for Romania painted in the country’s national flag and one for Britain’s second high-speed rail line. The company also makes machines to create much smaller tunnels for wires and pipes of all kinds.

We can help you find the best talent! Contact us today

Martin Herrenknecht grew up in the local town of Allmannsweier and founded the company in 1977 with a $20,000 loan from his mother. He started off small — creating machines to bore tiny tunnels for water lines or utility lines — but invested all his profits into ever bigger and more sophisticated machines. A big boring machine is an awe-inspiring sight not only because it’s so huge (more than 50 feet wide and a third of a mile long) but also because it’s a moving factory containing some 90,000 moving parts. As well as boring a hole, the device must put cladding rings into place to stop the tunnel collapsing, remove the displaced material (sometimes broken into small chips and sometimes liquified into something like toothpaste) on conveyor belts, and project itself forward, in some models using flippers modelled on the flipper-like arms of the king of the tunneling world (and bane of gardeners), moles.

Herrenknecht’s rise coincided with the golden era of globalization. The company built machines for the Moscow underground as well as the New York City one. It currently has seven facilities in China employing some 700 people. It is nevertheless adjusting fast to the new age. Dr. Herrenknecht fiercely rejected an offer from a Chinese company to buy his company. (The three biggest companies in the world are now in China.) He sacked his friend, former Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, from his board after Russia invaded Ukraine because of his pro-Putin apologetics. The company is increasingly looking beyond China to the rest of Asia and Latin America for its markets.

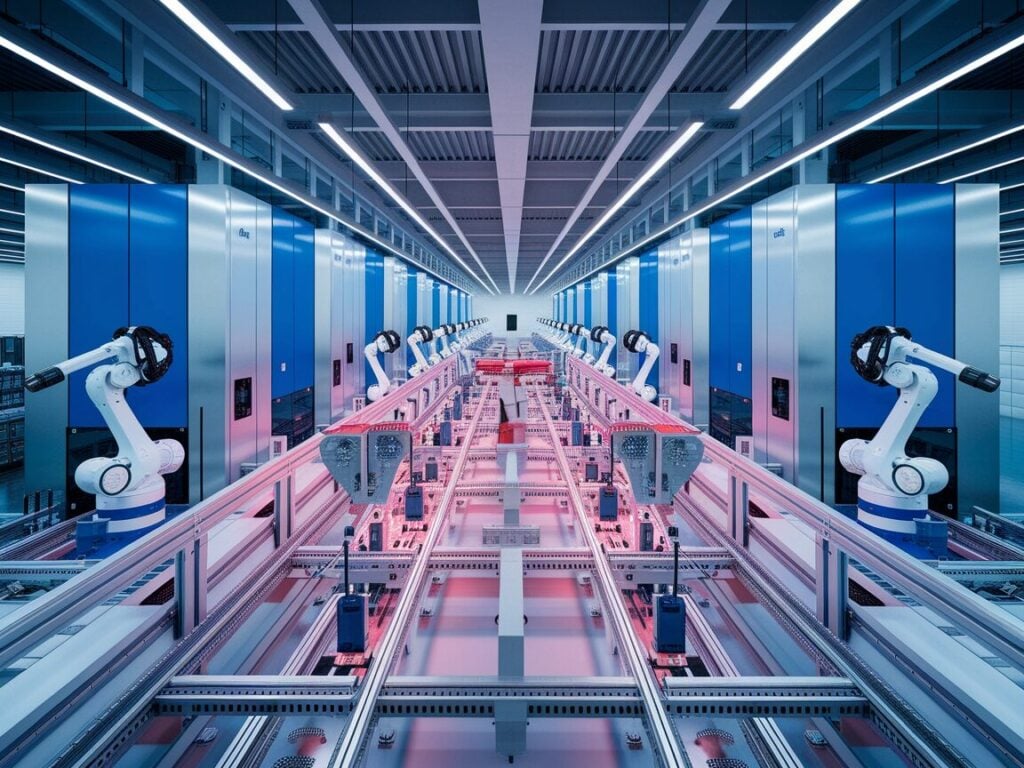

Scio Automation GmbH is a group of 10 medium-sized automation and robotics specialists buried in yet another small town, Frankenthal, near Mannheim, in the heart of the country’s wine region. (The region is rather less proud of another local product, Donald Trump’s grandfather, Frederick.) The group’s core business is to provide the know-how (hence “Scio” from the Latin “I know”) for automation. “We take machines and give them a brain so you don’t need a human,” says, the group’s CEO, Michael Goepfarth.

Goepfarth is hardheaded about the new era of globalization. He says that he came of age during globalization’s golden era, when markets were opening up and the riddle of politics had been solved. But when he worked for Daimler’s bus-making division in China in the early 2000s, he was shocked by the Chinese habit of cheating (the locals built a factory opposite his own and churned out copycat buses). He is now cautious about working in China: He makes sure he keeps his most vital information in Germany, refuses to set up permanent subdivisions in China, and only allows his employees to work with clients such as the big German car companies under strict conditions designed to prevent the theft of intellectual property. He is also amazed in retrospect that Western companies were so focused on reducing costs that they allowed 90% of the world’s supplies of microchips to be based on an island that the Chinese regarded as theirs by right.

Germany’s Main Trading Partners

Goepfarth thinks that a more tough-minded approach can be justified on economic as well as moral grounds: Working with corruption-prone Russian companies, however lucrative, is not worth the long-term trouble. He also thinks that the new era of globalization will allow companies to preserve economies of scale while bringing lots of benefits to his group. Regionalization will force companies to make their supply chains shorter and more efficient. (Companies that solve problems are often in favor of disruptions that create them.) Near-shoring will also oblige Western companies to replace expensive workers with machines. The new phase of globalization will multiply opportunities for a group that specializes in eliminating costs.

German Companies Are Most Bullish on North America

Wafios AG is hidden in yet another small town, Reutlingen, south of Stuttgart, the home of Mercedes-Benz and Porsche. The company is the oldest of the three, dating from 1893, and the least globalized, with 30% of its business in Germany. It specializes in a mind-boggling niche: producing the machines that bend wire and pipes or chains into the desired shapes. This is B2B business at its most abstruse, but something has to coil the 3,000 to 6,000 coils in the average car or bend the tubes that frame your office chair.

Wafios’s concession to the last age of globalization was to open two plants in China and allow them to produce cheaper machines for the emerging market. But the CEO, Uwe-Peter Weigmann, who grew up in East Germany, refuses to do business with Russia, a position that is strongly supported by his employees. He sees the future in terms of quality rather than quantity. The company’s focus is on improving its machines so that they can go faster, coiling and bending at ever more mind-boggling speeds, and produce a wider range of shapes and sizes from the same batch of metal, while also becoming easier to use (modern computer interfaces allow unskilled workers to operate machines that were once the preserve of master craftsmen).

He doesn’t think that price competition makes sense in a luxury market: A luxury carmaker shifted to a cheaper machine-maker only to come back with its tail between its legs when its customers started to complain about imperfections. Greenery is also a boon: He is producing a new line of machines that specialize in bending the intricate parts (often made of plastic or copper) that go into electric vehicles. The EV market now accounts for 15% of his sales, up from nothing five years ago, and he is confident that the momentum will increase.

It’s not clear exactly what the new age of globalization will entail — deglobalization, regionalization, trade wars or, perhaps most likely, a confusing mixture of more globalization in some areas and less in others — but, as our three examples illustrate, Germany’s hidden champions have three qualities that stand them in good stead for the storms to come.

Germany’s hidden champions – Three qualities

The first is a single-minded, it’s tempting to say monomaniacal, focus on being the world leader in their niches. “We know how to bend things,” says Weigmann, whose hobbies include 3-D printing and fixing up old cars. “Just drill and drill and dig and dig,” says a Herrenknecht employee of the company’s business plans. They routinely resist the temptation to branch out into related businesses, as Amazon is branching out into opening stores, for example; instead, they plow their profits back into discovering better technical solutions to their core business. This is a recipe for success in whatever version of globalization the world throws at us: If you can solve a problem better than anybody else, then the world, however configured, will beat a path to your door.

The second is complicated defenses against cheaper competition. The companies provide a combination of high-quality products and expert services that is hard to replicate. They pride themselves on generating a supply of well-trained workers through their vaunted training programs. They routinely dispatch young workers to sites around the world to provide advice or to learn their trade. They constantly talk with other Mittelstand managers about the latest challenges and opportunities.

They also pride themselves on the depth of their relationships. Mittelstanders safeguard the trust that they build up with their customers: They love to tell stories about resisting pressure to let one customer have a peek at a machine designed for another. The implication is that even in the unlikely circumstances that countries in the developing world can produce machines that match theirs, they will not be able to provide the same level of trust.

The Mittelstanders were not Panglossian. Many engineering courses in German universities have trouble filling their places and even then suffer from high dropout rates. The pace of government reform is glacial, particularly when it comes to digitalization. German efficiency coexists with striking inefficiency (your correspondent tried to take two trips by train while researching this article, only to find that the first train was late and the second, to the airport, was canceled, triggering chaos).

Germany’s Missing Workers

But the most striking thing about their attitude to globalization was the optimism. They see an upside to decoupling from China — the Chinese are unfair competitors, subsidizing their companies and stealing trade secrets, and are increasingly invading Western markets. They believe firmly not only that excellence will triumph in the end but also that the companies of the Mittelstand have a sustainable model for excellence: first-class training and incremental innovation. All very uplifting. A pity the authorities can’t make the trains run on time — or, indeed, at crucial moments, at all.

ARTICLE BY: Adrian Wooldridge – Bloomberg| Published: 04/11/2023